How Indian Attire, Food and Architecture Reflect Centuries of Cultural Exchange

Historian Sohail Hashmi highlights how Indian attire, food and architecture evolved through centuries of interaction, trade, and adaptation, showing shared cultural practices rather than rigid ideas of identity.

-

Indian attire evolved with foreign influences while retaining traditional rituals and unstitched garments

-

Indian cuisine shaped by global exchange, trade, and introduction of crops like potatoes and chillies

-

Architecture reflects environmental, technological, and regional factors more than rigid religious labels

Indian society’s traditions in clothing, cuisine, and architecture are the product of centuries of cultural exchange, rather than isolated or strictly indigenous developments, according to renowned oral historian, filmmaker, and cultural conservationist Sohail Hashmi.

Speaking at a webinar organised by the Indian History Forum (IHF) titled “The Story of Our Attire, Food and Architecture”, Hashmi traced the historical evolution of Indian lifestyle practices between the 12th and 18th centuries. He emphasized that contemporary debates often seek rigid definitions of “Indian” culture, but historical evidence reveals layered processes shaped by geography, climate, technology, trade, and human movement.

Indian Attire: A Blend of Tradition and Influence

Hashmi explained that India was among the earliest regions to cultivate cotton, giving rise to staple unstitched garments such as the dhoti, sari, and lungi, which remain central to ritual and cultural practices. Stitched garments, including the kurta, pyjama, kameez, blouse, and petticoat, arrived later through foreign influence, particularly after European introduction of scissors and tailoring techniques.

“These unstitched garments still play a key role in rites of passage related to birth, learning, marriage, and death,” Hashmi noted, “reflecting older ideas of ritual purity while showing how clothing adapts over time.”

Indian Food: A History of Exchange and Adaptation

Discussing cuisine, Hashmi highlighted the global roots of many foods considered quintessentially Indian. While staples like rice, wheat, and legumes are indigenous, several fruits, vegetables, and culinary techniques arrived through trade and empire.

Potatoes, chillies, and grafting methods brought by the Portuguese, and later encouraged under Mughal rule, transformed Indian diets. Hashmi also traced sugarcane’s journey from India to other parts of the world, illustrating how food history is linked to trade networks and global labour systems.

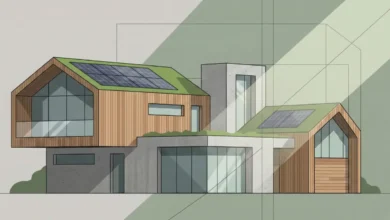

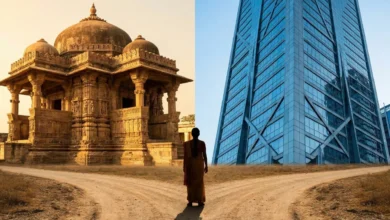

Indian Architecture: Beyond Labels

On architecture, Hashmi critiqued simplified colonial labels like “Hindu” or “Islamic” architecture, arguing that such classifications overlook the impact of environmental conditions, available materials, and technology. Drawing comparisons across Asia and Europe, he explained that domes, arches, and other architectural features predate organised religions and were adapted regionally over centuries.

“Migration, travel, and cultural exchange have always been central to human history,” Hashmi said. “Trying to separate Indian and foreign influence is historically misleading and diminishes the richness of our heritage.”